By Bob Currie, Recreational Boating Safety Specialist

By Bob Currie, Recreational Boating Safety Specialist

U. S. Coast Guard Auxiliary Station Galveston Flotilla

The master or person in charge of a vessel is obligated by law to provide assistance that can be safely provided to any individual in danger at sea (46 USC 2304). The type of assistance is greatly dependent on the ability of the assisting vessel’s master to provide assistance without endangering his or her own vessel or the safety of its passengers. One of the most common forms of assistance is to provide a tow to a disabled boat. Although towing might seem an easy prospect, there are many inherent dangers to doing so, and safety is the most important consideration when deciding to provide a tow.

This column is intended to be a very general discussion of towing and is not intended to be a primer for towing. No boat operator is required by law to provide towing assistance. Sometimes the best assistance you can give is to notify the Coast Guard about the disabled vessel. If you do decide to tow another boat, there are some basic things you should know.

The Station Galveston Flotilla of the US Coast Guard Auxiliary operates out of the USCG Station Galveston base on Galveston Island. They aid the Coast Guard by providing maritime observation patrols in Galveston Bay; by providing recreational boating vessel safety checks; and by working alongside Coast Guard members in maritime accident investigation, small boat training, providing a safety zone, Aids to Navigation verification, in the galley, on the Coast Guard Drone Team and watch standing.

Important Considerations

Before providing a tow to another vessel, the master of the towing vessel must carefully assess the situation to ensure that the tow can be safely provided. First, the situation should be non-distress; that is, no person aboard the disabled vessel is in need of immediate medical attention and the disabled vessel is not taking on water or otherwise damaged in a way that would hinder being towed.

Second, ensure that the wind, weather, and sea conditions are such that the vessel can be safely towed by the prospective towing vessel. There is always the danger of one of the boats being capsized by the considerable forces that apply to towing.

Third, ensure that the towing vessel has the proper gear needed to ensure a safe tow. Although I have seen waterski tow ropes used to tow boats, such ropes are generally too light to handle the shock loads set up by towing in open waters. You might get by using a skier tow rope on a smooth river, but even one foot waves can set up shock loading on a waterski tow rope, resulting in snapping the line and putting occupants of both boats in danger of being hit by the line if it breaks under heavy load.

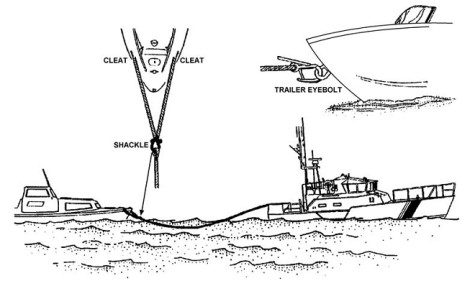

Bridle and Trailer Eyebolt Tow Rig Connection

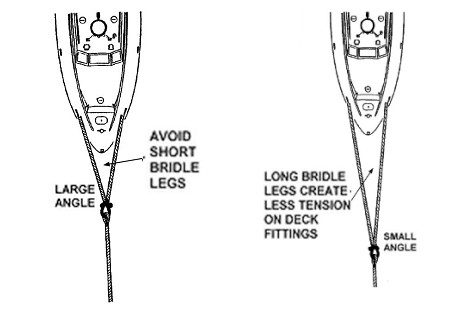

The most common towing method is towing a disabled boat from astern. Another method is towing alongside. We will discuss towing from astern. There are two basic methods used to tow a disabled boat from astern. One method is to connect the tow line to the trailer eyebolt on the disabled vessel. The other method is to use a bridle attached to cleats near the bow of the disabled vessel that allow an equal pull to be asserted on them. If the pull is not equal, then either or both boats could be capsized due to the great forces generated by towing. When using a bridle, avoid short bridle legs, as they create more tension on deck fittings.

On smaller, trailerable boats, the trailer eye is frequently the sturdiest fitting available to attach a tow rig. Attaching a towline to the trailer eye is a very dangerous technique. It requires the towing vessel to maneuver very close to a distressed boat and requires crewmembers to extend themselves over the side between two vessels, or under the flared bow sections of the distressed boat. There is a specialized skiff hook designed to attach the tow line to the trailer eye. If you do not have one of those hooks, the bridle method should be used for towing.

The Tow

Once you have secured a tow line to both vessels, there are several considerations in actually performing the tow. There are separate procedures for starting the tow, changing heading, and minimizing forces when towing another vessel.

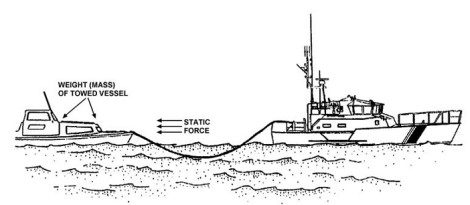

Static Force

Static force causes a towed vessel to resist motion. The displacement or mass of a towed vessel determines the amount of force working against the vessel. The assisting vessel must overcome these forces before the towed vessel moves. Inertia and the moment of inertia are two different properties of static forces that cause resistance in towing vessels.

Overcome the effects of static forces by starting a tow slowly, both on the initial heading or when changing the towed vessel’s heading. A large amount of strain is placed on both vessels, their fittings, and the towing equipment when going from dead-in-the-water to moving in the desired direction and at the desired speed. Extreme caution should be used when towing a vessel of equal or greater mass than the assisting vessel. In such situations, the assisting vessel strains the capacity and capability of its equipment, requiring slow and gradual changes.

Procedure for Starting the Tow

The goal when starting the tow is to overcome the static force of the towed vessel in the water without causing damage to either the towed or the towing vessel. It is at this point that one or both boats could be capsized. It is important to start the tow using the same heading as the disabled vessel. If you try to both start the tow and change the heading at the same time, the lateral forces set up could capsize either or both vessels. Also, if force is placed unequally on the bow cleats of the boat to be towed, the cleat could be wrenched from the deck and become a deadly projectile. Use the following steps when starting the tow:

- Apply the towing force on the initial heading to gradually overcome the towed vessel’s inertia. Keep an even tension on both legs of the bridle.

- As the towed vessel gains momentum, slowly and gradually increase speed.

- To change the tow direction, make any change slowly and gradually after the towed vessel is moving.

Changing the Towed Vessel’s Heading

The moment of inertia occurs when a towed vessel resists effort to turn about a vertical axis to change heading. The larger the vessel, the more resistance there will be in turning the vessel. Unless necessary in a case of immediate danger, do not attempt to tow a distressed vessel ahead and change its heading at the same time. Apply turning force gradually and slowly. Once making way, the effect of static forces diminishes and dynamic forces come into play. Once the vessel’s heading begins to change, it wants to keep changing in that same direction. The faster the towed vessel’s heading changes, the harder it is to get the tow back to moving in a straight line.

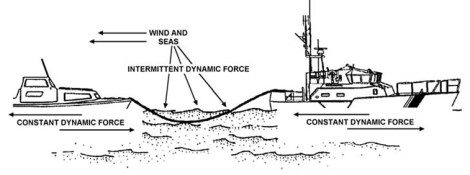

Dynamic Forces

Dynamic forces occur once the towed vessel is moving. They are based on the towed vessel’s characteristics (shape, displacement, arrangement, rigging), the motion caused by the towing vessel, and the effects of waves and wind. Below is a list of the types of forces that affect the tow. A full discussion of these forces is beyond the intent of this column, but knowledge that they exist and can affect the safety of the tow is essential. The dynamic forces set up during a tow include:

- Momentum

- Angular Momentum

- Frictional Resistance

- Form Drag

- Wave-Making Resistance

- Wave Drag

- Wind Drag

- Spray Drag

- Shock-Load

Combination of Forces and Shock-Load

During a towing evolution, the boat crew rarely deals with only one force acting upon the tow. The crew usually faces a combination of all the forces, each making the situation more complex. Some individual forces are very large and relatively constant. Crews can usually deal with these safely, provided all towing-force changes are made gradually. When forces are changed in an irregular manner, tension on the tow rig starts to vary instead of remaining steady. “Shock-load” or “shock-loading” is the rapid, extreme increase in tension on the towline, which transfers through the tow rig and fittings to both vessels. Shock-loading may cause severe damage to both towing and towed vessels and overload a tow rig to the point of towline or bridle failure. Shock-loading could also cause momentary loss of directional control by either vessel and could capsize small vessels. Extreme stress is put on the tow rig in heavy weather when the tow vessel and the towing vessel do not climb, crest or descend waves together. Vessels in step will gain and lose momentum at the same time, allowing the towing force to gradually overcome the towed vessel’s loss of momentum, minimizing shock-loading. To get the vessels in step, lengthen rather than shorten the towline if possible. Slowing down lowers frictional resistance, form drag, and wave-making resistance. Reducing these forces will lower the total tow-rig tension.

Underway With the Tow

The best course to safe haven is not always the shortest distance. A course that gives the best ride for both vessels should be chosen. At times, the vessels may have to tack (run a zigzag type of course) to maintain the best ride. A firm understanding of the dynamic forces in towing helps to ensure a safe tow. In head seas, where waves come from directly ahead, reducing speed also reduces wave drag, spray drag, and wind drag, lowering the irregular tow rig loads. It is best to avoid running in head seas if possible. If possible, try to ride waves at a 45 degree angle. Have a crew member of your boat watch the towline so they can let you know of any dangerous situations that may develop. Warn the passengers of boat boats to stay our of the path of the towline to avoid being struck if the line snaps.

Coast Guard Notification

Before you attempt to tow another vessel, notify the Coast Guard of the situation, being sure to give your current location, the condition of both vessels, the number of persons aboard both vessels, and the destination of the tow. When the tow is complete, notify the Coast Guard.

Summary

Towing another vessel that has become disabled should only be done after weighing all safety considerations. The sea conditions must be favorable to the tow, you must have sufficient tow line that is in good shape, and you must have an understanding between the occupants of the vessel to be towed and the occupants of the towing vessel as to how the tow will be conducted. Persons on both vessels need to stay out of the path of the tow line should it break,, and there should be an agreed to signal to disengage the tow if it becomes unsafe.

For more information on boating safety, please visit the Official Website of the U.S. Coast Guard’s Boating Safety Division at www.uscgboating.org. Questions about the US Coast Guard Auxiliary or our free Vessel Safety Check program may be directed to me at [email protected]. SAFE BOATING!

[Oct-26-2021]

Posted in

Posted in