By Bob Currie, Recreational Boating Safety Specialist

By Bob Currie, Recreational Boating Safety Specialist

U. S. Coast Guard Auxiliary Station Galveston Flotilla

Whenever I perform a Vessel Safety Check on a recreational boat, after I complete the inspection for the required items I then get into the Coast Guard recommendations, including the one on fuel management. Good fuel management allows you to go farther on a tank of gas while maintaining the recommended fuel reserve. This column will discuss fuel management and other considerations for going the distance.

Destination Tokyo

Destination Tokyo is movie from 1943. The premise is that in order to provide information for the first air raid over Tokyo, a U.S. submarine would sneak into Tokyo Bay and place a spy team ashore. That’s a long haul for any vessel, especially a submarine, but fuel management was not generally a problem for submarines during World War II, as the typical submarine range was 15,000 to 25,000 nautical miles, depending on the class of sub. Fuel management for recreational powerboats, however, is the number one issue when it comes to going the distance.

U.S. Coast Guard Fuel Management Recommendation

The basic fuel management method recommended by the Coast Guard is the Rule of Thirds. You should not use more than one third of your fuel to get out to where you are going. That leaves you one third to get back and one third for reserve. If you are going from point A to point B and not returning, then you should not need to use more than two thirds of your fuel to get there. In general, it takes more fuel to get back than you used to get out. There are two reasons. First, once you get where you are going, you often burn some fuel moving around (especially if fishing). Second, you usually go out using the prevailing winds and you fight those winds coming back in.

Fuel Management Table

Boaters should take special precautions to avoid running out of fuel. The Coast Guard Rule of Thirds formula requires you to have good knowledge of your fuel consumption under different conditions. Your engine manufacturer may be able to help you by providing a fuel consumption table as a starting point. You should modify such table as necessary to fit your boat and load. This link will help you get started if your engine is an outboard model:

Before you create your own fuel consumption table, it is wise to use your engine manufacturer’s reported maximum gallons per hour (GPH) usage as a starting point. The Yamaha interactive guide shown is based on moderate loads for a hypothetical boat, but it gives you a pretty good idea of the fuel usage based upon RPMs.

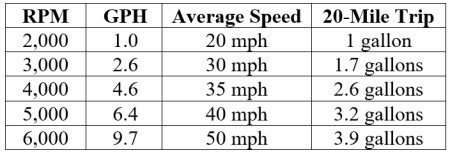

Sample Yamaha 115 Fuel Consumption Table

I used the website above to help me create a hypothetical fuel consumption table for my boat, which has a 115 hp Yamaha. The website gave me gallons per hour (GPH) at certain RPM and I determined the average speed with my usual load of two people with fishing gear.

It is obvious from the fuel consumption table that you sacrifice fuel efficiency for speed. Notice that my increase in speed with increase in RPM is not perfectly linear. If the speed vs. RPM rates were linear, I would be moving 60 mph at 6,000 RPM. Using this table, you can determine a speed that will get you back to the dock with the least amount of fuel required. This does not take into account fighting a headwind or heavier seas coming back to the dock. Of course it was smooth going out and rough coming back in. That is the way sea weather works. The different heating rates of water and land create winds that push seaward, and those winds kick up the waves.

Effect of Trim

The trim of your engine is another variable in the fuel consumption estimate. My table is based on moderate trim rather than full trim. Your boat does not handle chop well with full trim, so you need to use moderate trim when creating your fuel consumption table. Never use maximum performance when creating your fuel table. As you trim your boat up, fuel consumption rate usually decreases, but trimming your boat up fully in choppy water reduces your stability to the point you could capsize or swap ends. End swapping occurs when a chine digs in at a time when the boat is not fully horizontal and is balanced on the tail instead. Older model tunnel boats are the most likely to swap ends when they become unstable. Either situation always leads to ejection of passengers and increases the likelihood of death or injuries as a result.

Single vs. Twin Engines

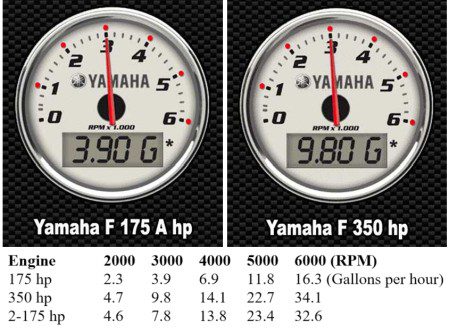

One might assume that two engines would automatically consume more fuel than a comparable single engine, but that is not always the case. For instance, as the chart below shows, two 175-hp Yamahas consume slightly less fuel at most throttle settings than a single 350-hp Yamaha.

If you operate your boat on the principle of the Coast Guard recommendation of “one third of your fuel to go out, one third to get back, and one third as reserve,” you stand a good chance of making it back on one engine. But keep in mind that you will most likely have to operate that single good engine at or near full RPM, and that pushes your fuel consumption up considerably.

Getting on Plane

One of the most important things to consider when purchasing a twin engine craft is whether or not the boat is capable of getting on plane with a single engine. If you can’t get on plane with one engine, that 60-mile trip back in will stretch from three hours to possibly eight hours or more, depending on what speed you will be able to make. A boat that is not on plane is much harder to navigate in rough water. The time to find out if your boat will get on plane with just one engine is before you lose an engine. If a boat has a planing hull, then the manufacturer’s recommended horsepower for that boat starts with enough horsepower to get the boat on plane. That being said, that lowest horsepower rating takes into consideration the best case scenario of one person aboard with no extra gear. Not much chance of that being the case, is there? So, consider a good margin of error when choosing the horsepower of your twin engine craft. If the minimum recommended horsepower is 200 hp, you might not be able to get that boat on plane with one 100 hp engine if you are loaded with passengers and gear. Take that salesperson up on the offer of an on the water demonstration, then ask him to get the boat on plane with one engine. You need that peace of mind. Once you know your boat will operate on plane with one engine, there are some other things you can do to help get on plane, stay on plane, and get back home safely using just one engine.

Raise the Dead

Engine, that is. If possible get that dead engine’s lower unit out of the water to help eliminate drag and also help with maneuvering. It will be harder steering the boat with the good engine being offset from center, so any help you can get is welcomed.

Weight Forward

You should know it is harder to get on plane when everyone is sitting at the back of the boat. Outboards tend to squat in the stern and rise in the bow when coming out of the hole. Most boats have a recommended seating chart, and that chart is designed to help you get on plane and safely maneuver the boat at speed. Moving the weight forward is even more important when you are down an engine. It’s not just the passengers you need to move. Move heavy gear such as ice chests forward. Once you get on plane, the passengers may be able to move toward the stern to get comfortable. It takes a lot of energy to get up on plane, but once you are there it takes less energy to maintain it.

Lighten Up

If you have shifted the weight forward and you are still having trouble getting on plane, you may need to lighten up. Empty out built-in ice chests and freshwater tanks located at the stern if you are having trouble getting on plane. Water weighs 8.3 pounds per gallon. If you empty out a 30-gallon live well, it has the same benefit as throwing your brother-in-law overboard (come on, now- lighten up, pun intended). If you have fish on ice, you can reduce the amount of ice and still keep them cool enough.

Tilt and Trim

In order to come out of the hole and get up on plane you will need to have the trim in all the way. That position helps raise the stern while tending to keep the bow down. Once you have the boat on plane, try trimming the engine out in small increments. This will raise the bow slightly and help reduce drag. Once you are up on plane, do not make any sharp turns, as this may bend the tie bar between the engines. If you have trim tabs, use them to help pop up out of the hole. Once you are on plane, use them to help keep the boat from heeling over to one side due to the offset torque from the one good engine. Apply down tab to the lower side to level the boat and keep you on an even keel.

Summary

When planning a trip on the water, be sure to follow the Rule of Thirds as recommended by the Coast Guard. Know your boat and engine’s fuel consumption rate, and prepare a fuel consumption table to help take the guess work out of your planning. If you do get caught short on fuel, notify the Coast Guard immediately, and keep them up to date on your progress back to shore. Slow down to a point where fuel consumption is as its best, and you will stand a good chance of getting back in. Go the distance that you know you can reasonably determine. Don’t stretch it.

[BC: Mar-7-2023]

Posted in

Posted in