By Bob Currie, Recreational Boating Safety Specialist

By Bob Currie, Recreational Boating Safety Specialist

U. S. Coast Guard Auxiliary Station Galveston Flotilla

The topic today isn’t “what’s happening in the Gulf of Mexico.” Rather it is about the relative movement of water in a pattern we call a current. There is another type of current that is important in navigation: air currents, otherwise known as winds.

The Station Galveston Flotilla of the US Coast Guard Auxiliary operates out of the USCG Station Galveston base on Galveston Island. They aid the Coast Guard by providing maritime observation patrols in Galveston Bay; by providing recreational boating vessel safety checks; and by working alongside Coast Guard members in maritime accident investigation, small boat training, providing a safety zone, Aids to Navigation verification, in the galley, on the Coast Guard Drone Team and watch standing.

Wrestling Match of the Century: Wind vs. Current

The two main forces on a boat in the water are wind and current. All things being equal, current has a much greater effect on a boat. Think of a wrestling match between the two: “Ladies and gentlemen, in this corner we have Wind, weighing in at 5.5 quadrillion tons, and in this corner we have Current, weighing in at 1.5 quintillion tons.”

Those weights represent the entire mass of air and the entire mass of water on Earth. That is a big difference in mass. A quadrillion is 1 with 15 zeroes, while a quintillion is a 1 with 18 zeroes. That’s like putting Tom Thumb (Wind) up against Andre the Giant (Current). Andre is going to win every time unless Tom develops some type of advantage such as a force multiplier. You know, like when Popeye eats his spinach and beats Bluto up. The force multipliers we are talking about in this case are the sail, developed in ancient times but still applicable today, and the engine, developed in the last couple of centuries. You could also mention the oar, used by Vikings (along with their sails) and other people to move against the current. The fastest non-engine-powered navigation uses a combination of favorable current and favorable wind, but sometimes you only have one or the other to take you where you want to go.

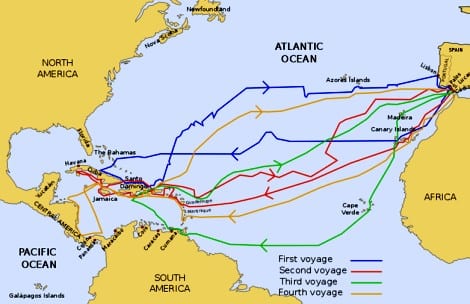

When Columbus headed back to Europe after that first voyage, he didn’t beat his way back by endless tacking against the wind that propelled him to the New World, instead, he found a favorable wind to get back to Europe. Even before he set out Columbus was aware of different prevailing winds. He knew that he could travel westward using the Trade Winds, and he knew he could return using the Prevailing Westerlies. He had the right route, but he reached the Caribbean rather than his destination of China.

source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=8849049

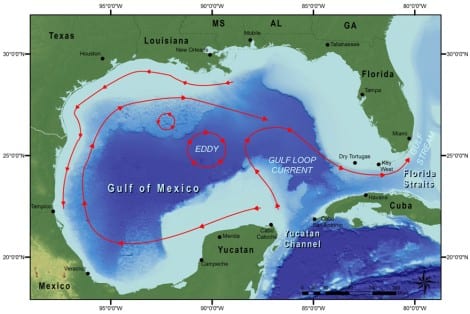

Gulf of Mexico Current Events

The map above briefly shows the prevalent currents found in the Gulf of Mexico. The actual currents, although they follow this general pattern, are much more highly extensive. There are several important reasons for mapping ocean currents in general. These currents play a big part in determining the paths of storms such as hurricanes. NOAA uses current predictions to predict the paths of hurricanes. The currents in the Gulf of Mexico are influenced by the Coriolis effect and the shape of the Gulf basin. One current begins near the Yucatan Peninsula and rotates clockwise toward the tip of Florida. This is called the Gulf Loop Current. On the far eastern side of the Gulf of Mexico, the Florida Current and the Gulf Loop Current combine and flow between the southern tip of Florida and Cuba. This flow of water forms the Gulf Stream. It is joined and strengthened by an Atlantic current (the Antilles Current). The Coriolis effect causes the Gulf Loop Current to rotate clockwise, while the shape of the basin allows the loop current to flow into the Gulf Stream.

Coriolis Effect

The Coriolis effect describes the pattern of deflection taken by objects not firmly connected to the ground as they travel long distances around the earth. The Coriolis effect makes things like currents of air and water appear to move at a curve as opposed to a straight line.

The Coriolis Effect has several properties:

- It causes winds to curve to the right in the northern hemisphere.

- It causes winds to curve to the left in the southern hemisphere.

- It increases with increasing Latitude (zero at the equator).

- It increases with increasing wind speed.

- It is effective only over long distances (NOT in sinks!).

- Although it is not a true force, it behaves like one.

A good example of how the Coriolis effect works is to take a revolving disk and try to draw a straight line from the center of the disk to an outer edge using a straight rule. As the disk rotates, the marking curves, even though you are guiding the pen with a straight rule.

Real Time Ocean Forecasting System (RTOFS)

RTOFS is the Real Time Ocean Forecasting System. NOAA’s Real Time Ocean Forecast System (RTOFS)–Atlantic is a data-assimilating nowcast-forecast system operated by the National Weather Service’s National Centers for Environmental Prediction (NCEP). The model runs daily, producing a forecast out to 120 hours. Two sets of RTOFS output files are provided for distribution: files that contain three-dimensional fields reported on standard depths with a 24-hour output time step and surface-only files with a 1-hour output time step. One application of RTOFS is to determine the paths of objects embedded in the ocean such as the path of oil in an oil spill. Another is to assist in hurricane strength determination. Water temperatures are higher in the Gulf Stream. If a hurricane is forecast to pass over the warmer Gulf Stream water, the warmer water could have a major impact on the strength of the hurricane. The RTOFS maps of the currents of the Gulf Stream and its associated warm and cold eddies can be helpful in determining the strength of the hurricane. RTOFS produces now-casts and forecasts of sea levels, ocean currents (including direction as well as speed), water temperatures and salinity. The system takes into account deep waters as well as coastal waters.

Exploration of the Gulf Loop

The Gulf Loop Current has the largest effect on currents in the Gulf of Mexico. It has only been recently that extended studies of the Gulf Loop Current have been made. NOAA Ship OKEANOS EXPLORER has been used extensively for exploring and mapping currents in the Gulf Loop. Surface currents are ocean currents in which the moving water lies between the surface and a maximum depth of about 500m. Currents that are no deeper than 200m are usually caused by the wind pushing on the water. Currents as deep as 500m usually are caused by forces associated with the rotating Earth and are called geostrophic (Earth-turned) currents. The Gulf Loop flows into the Gulf of Mexico from the Yucatan Strait and exits through the Florida Strait. Sometimes the Gulf Loop barely intrudes into the Gulf, and other times it extends deeply into the Gulf. When the loop is extended, it becomes unstable and spins off eddies which rotate clockwise as they drift westward. Some of the eddies contain warm water and sometimes they contain cold water. An eddy, sometimes called a whirlpool, is a current of air or water running back, or in the opposite direction to the main current. Eddies can be hundreds of miles wide.

Deep Thoughts

The Gulf of Mexico is about 3800m deep at its deepest point. That’s about 12,500 feet, or two and a third miles deep. That would be some tough anchoring, especially if you use the depth to anchor line ratio of 7:1. Although you might think that the Atlantic Ocean has the biggest influence on water conditions in the Gulf, it is actually the Gulf Loop coming in from the Yucatan Strait and exiting the Florida Strait that sets up conditions in the Gulf. The Yucatan Strait is about 2000m deep, but the Florida Strait is only about 800m deep. This means that the deep water in the Gulf flows in from the Caribbean, not directly from the Atlantic. In effect, the islands of the eastern Caribbean form a very leaky wall with many shallow gaps, but only a few deep gaps. Just as this wall limits deep water flow, it might partially isolate animal populations in the deep Gulf from the populations in the larger and deeper Atlantic (8400m, or five and a quarter miles deep). The Atlantic is not the deepest ocean. The Pacific is 7 miles deep.

Ben Franklin: Oceanographer

Benjamin Franklin is known as one of the shapers of the U.S. Constitution, and is one of our most famous founding fathers. He is also the first person to chart the Gulf Stream. The Gulf Stream is an ocean current that moves clockwise through the Gulf of Mexico and up along the eastern coastline of North America. Because it altered sailing patterns and shaved time off a typically long and treacherous trip, the Gulf Stream was instrumental in the colonization of the Americas. To honor Ben Franklin’s contribution to oceanography a big eddy that formed by the Gulf Loop in 2010 is called Eddy Franklin. If you are planning to try to fish in a big eddy, be sure to take the water temperature. Warm water eddies have less marine life than cold water eddies due to loss of nutrients due to higher temperatures.

Coast Guard Use of Currents

When someone is lost at sea, time is of the essence. Knowing the speed and direction of currents can help the U.S. Coast Guard conduct search and rescue operations with greater accuracy. The Integrated Ocean Observing System uses high frequency radar systems to develop maps of surface currents for the Coast Guard to use in their operations. The Integrated Ocean Observing System is a national-regional partnership working to provide new tools and forecasts to improve safety, enhance the economy, and protect our environment. Integrated ocean information is available in near real time, as well as retrospectively. Easier and better access to this information is improving the ability to understand and predict coastal events such as storms, wave heights, and sea level change. Such knowledge is needed for everything from retail to development planning. These maps may also be used to support other scientific work, such as oil spill response, harmful algal bloom monitoring, rip current location, and water quality assessments.

Way Down Yonder in the Garbage Patch

Some will get the heading for this section; some won’t. It is a play on words from the old nursery rhyme “Way Down Yonder in the Papaw Patch.” The next time you are on the Gulf of Mexico drinking water from a plastic bottle, I want you to think about where that plastic bottle would end up if you were to throw it overboard after emptying it. It isn’t just going to sit there. It is going to end up where the current takes it. In most cases that would be what is called a garbage patch. A garbage patch is a floating island of plastic and other debris brought into existence by prevailing currents. Many of these garbage patches reside in the Gulf of Mexico. They aren’t stationary but move about with the currents. Some reside in general areas, and the Coast Guard even uses their knowledge of garbage patch movements to predict where a vessel at sea might end up. If you have ever seen a garbage patch then you know what I am talking about. If you have not seen one, it is hard to describe the extent of plastic debris, much of which is discarded water bottles, that you encounter in a garbage patch. The big question is which will we run out of first: plastic or ocean.

Summary

Two-thirds of our planet is covered by water. That water is constantly moving in often predictable patterns we call currents. Knowledge and use of currents lead to the discovery of America and exploration of the world in general. Recreational boaters use both winds and currents to travel on the water. If you are lost at sea, the Coast Guard will use its knowledge of air and water currents to help rescue you.

For more information on boating safety, please visit the Official Website of the U.S. Coast Guard’s Boating Safety Division at www.uscgboating.org. Questions about the US Coast Guard Auxiliary or our free Vessel Safety Check program may be directed to me at [email protected]. SAFE BOATING!

[Oct-5-2020]

Posted in

Posted in