By Bob Currie, Recreational Boating Safety Specialist

By Bob Currie, Recreational Boating Safety Specialist

U. S. Coast Guard Auxiliary Station Galveston Flotilla

The Texas coastline is 367 miles long. Many people think that the coastline is one long beach, but in reality it is broken up by many bays, channels, and rivers, some of which are navigable and some are not. As for the navigable channels, some are natural and some are man made. So, this article will not be about sitting in front of your TV flipping through channels to find an episode of The Real McCoys that you haven’t already seen. Instead, we will talk about navigating the many channels in our area.

The Station Galveston Flotilla of the US Coast Guard Auxiliary operates out of the USCG Station Galveston base on Galveston Island. They aid the Coast Guard by providing maritime observation patrols in Galveston Bay; by providing recreational boating vessel safety checks; and by working alongside Coast Guard members in maritime accident investigation, small boat training, providing a safety zone, Aids to Navigation verification, in the galley, on the Coast Guard Drone Team and watch standing.

Why Do We Have Channels?

The channels we are talking about are mostly manmade channels. If you were to go back in time far enough you would find that when it comes to navigating our bays and inlets you couldn’t get there from here because the water was too shallow to navigate. That is because over time natural bays tend to be filled in with silt from the rivers that feed them. The method used to create channels and harbors and to keep them navigable is by dredging.

History of Dredging

Oh, dredging goes way, way back, probably to prehistoric times. There are records of dredging the seven arms of the Nile River going back to 4000 BC. That’s six thousand years ago. The most important use of dredging in the old days was to create harbors for ships and to keep the harbors deep enough to be used. During the Renaissance Leonardo DaVinci drew a design for a drag dredger. The simplest method of dredging was to drag a bucket through the water, collect mud and silt, and redeposit it to help build up the shore. Chart makers used dredging records to indicate navigable channels. The dredged areas are periodically assessed and mapped, as the filling in action of the rivers is constant. Even the movement of ships through a channel adds to the filling in of the channel.

Local Dredging

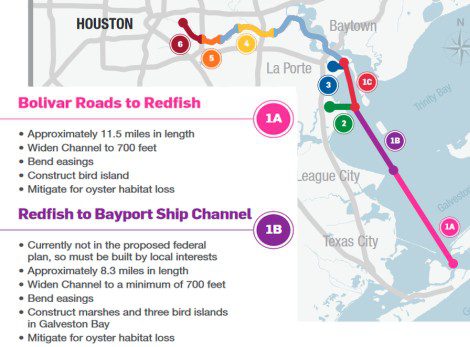

Local dredging occurs constantly in the Houston Ship Channel (HSC) and the Intracoastal Waterway. These channels support commercial shipping. Since 2010 the Houston Port Authority has been planning a project to widen and deepen the Houston Ship Channel so that the largest supertankers and container ships can navigate the channel. At this time the largest ships can navigate the HSC, but only if opposing traffic is shut down during the time they are using the channel. Below is a partial summary of the plan to widen and deepen the HSC.

Finding the Right Channel

When you want to travel to a certain location in your car, you look at a map to find the right roads to get you there. When you want to travel to a certain location on the water, you look at a chart to find the right route. It’s not as simple as traveling a straight line on the water. You have to know where the dangerous areas are located; this includes shipwrecks, shoals, rocks, and shallow areas that are unnavigable. In many cases you will have to travel through a channel to get where you are going. You will either need a paper chart or your chart plotter to help you find the right channel. There are no street signs out on the water. Instead, there are aids to navigation, called ATONs for short. Just as there are private streets, there are also private channels, and the aids to navigation for private channels are called PATONs (private aids to navigation).

Red Right Returning

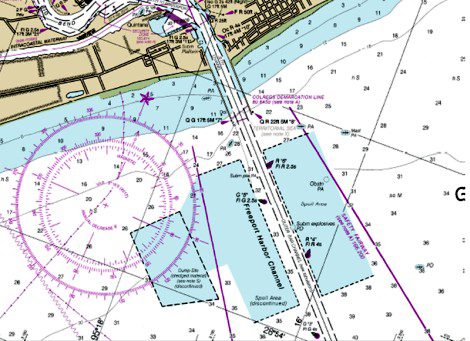

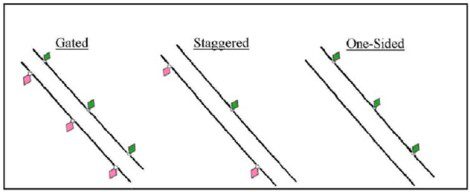

All sailors know that when returning from the sea, using the channel markers to guide them they keep red ATONs to their right (starboard) and green ATONs to their left (port). On this section of Chart 11322, showing the Freeport Harbor Channel, the little icons that look like exclamation points are the channel markers. The code beside each ATON tells you a little about it. G “5” Fl G 2.5s means that this is marker 5, it is green, and at night it flashes green every 2.5 seconds. In this channel the ATONs are staggered, but in many channels the ATONs are directly across from each other (gated), or there may be markers only on one side of the channel (one-sided). Red ATONs are always even numbered, and green ATONs are always odd numbered. The closer you get to shore the more often the ATONs flash. The two ATONs at the edge of the jetty in this chart section have a quick flashing pattern. If you notice that the flashing patterns start to have longer periods of darkness, then you have gotten turned around and are headed to sea.

The U.S. Aids to Navigation System

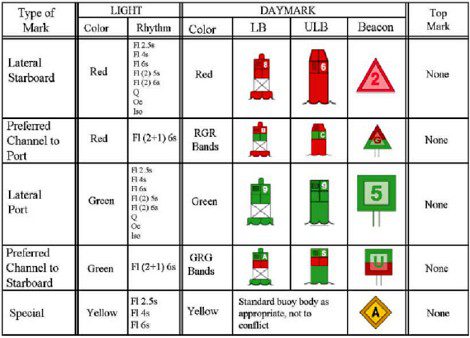

The U.S. Aids to Navigation System, also know as the Lateral System of Navigation, is designed for use with nautical charts. The exact meaning of an ATON may not be clear to the mariner unless the appropriate chart is consulted, as the chart illustrates the relationship of the individual ATON to channel limits, obstructions, hazards to navigation, and to the total ATON system. This article is intended to just introduce the Lateral System to the reader; it is not designed as a course on ATONs. One of the best ways to familiarize yourself with ATONs is to take a Safe Boater course. The chart below illustrates the most common signals found in the U.S. Aids to Navigation System.

Buoys and Beacons

Buoys are floating ATONS. They are moored to the seabed by sinkers with chain or other moorings of various lengths. Mariners attempting to pass a buoy close aboard risk collision with a buoy swinging about on its chain or collision with the obstruction which the buoy marks. Mariners must not rely on buoys alone for determining their positions due to the factors limiting buoy reliability. Buoy positions on charts are approximate positions only. Buoy moorings vary in length. The moorings define a watch circle, and buoys can be expected to move within this circle. If a buoy were held tightly to the seabed, then it would be covered during high tides. The extra length of the mooring chain allows the buoy to float freely at high tide.

Beacons are ATONs which are permanently fixed to the earth’s surface. They range from large lighthouses to small single-pile structures and may be located on land or in the water. Lighted beacons are called lights (LB on the chart below), and unlighted beacons are called day beacons (ULB on the chart below). Beacons exhibit a day mark. For small structures they are colored triangles or squares which make an ATON readily visible and easily identifiable against background conditions.

Warning! Warning! Danger Will Robinson!

Will Robinson may have been lost in space, but he had Robbie the Robot to warn him of danger in time to avoid it some of the time. We don’t have robots that can do that on the water, although some chart plotters are sophisticated enough that you can program them to warn of proximity to spots you have programmed into the chart plotter. The chart programmed into your chart plotter (or the physical chart itself) does warn of dangers known at the time the chart was made. The most common danger is shallow water. Shallow water is, of course, mostly found close to shore, but in bays where silt is actively deposited from rivers flowing into the bay, shallow water can be found just about anywhere outside of a well-maintained and marked channel.

Charts also mark certain obstructions, both above water and below the surface. If you look at the section of Chart 11322 above, you will notice a few football shaped icons. Those are shipwrecks. Shipwrecks and other obstructions may appear above the surface at low tides and be covered during high tides. The prudent mariner will stay within a marked channel as much as possible, and operate carefully outside of marked channels. If you do strike something in the water and begin taking on water, notify the Coast Guard immediately. Don’t wait until you are sinking because you can’t bail water faster than you are taking it on. Early notification gives the Coast Guard time to prepare for a possible rescue. We are just as happy as you are when you are able to make it back to port unassisted.

Summary

When you are navigating in the Houston-Galveston area, use well-marked and maintained channels as much as possible. You cannot look out across a vast bay and determine where the shallow water dangers are. Unintentional grounding is one of the most common marine accidents the Coasty Guard responds to. The dangers of an unintentional grounding are ejection of passengers causing injury or death, and damage to the hull leading to sinking of the vessel. You can reduce your chances of unintentional grounding significantly be operating within a charted channel.

For more information on boating safety, please visit the Official Website of the U.S. Coast Guard’s Boating Safety Division at www.uscgboating.org. Questions about the US Coast Guard Auxiliary or our free Vessel Safety Check program may be directed to me at [email protected]. SAFE BOATING!

[Sept-28-2010]

Posted in

Posted in