By Bob Currie, Vessel Examiner

By Bob Currie, Vessel Examiner

U. S. Coast Guard Auxiliary Station Galveston Flotilla

We recently had a boat end up on the rocks at the Galveston North Jetty. Fishermen like to get as close as possible to the rocks in order to get the fish that hide there. Sometimes they get too close. Even though the operator in this event had placed his anchor, he failed to ensure that it was holding and he quickly found his boat destroyed by being pounded on the rocks. Luckily a search was underway for another overdue boater and a station boat happened to see his boat on the rocks. This column is about anchors and anchoring, which is a useful skill in areas like jetties.

Anchor and Rode

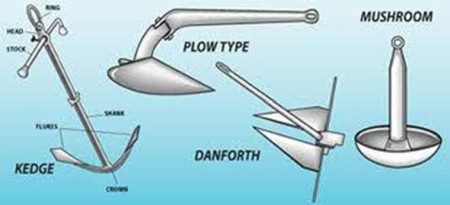

Anchors are important equipment for all boats. They allow you to remain in one spot and fish, swim, or just relax and enjoy the water. Anchors also are an important piece of safety equipment to keep the boat from drifting into danger or running aground. Boaters should make sure that their boats are equipped with an anchor of the appropriate type, size and weight for their vessel, as well as the appropriate type for the kind of bottom that prevails in the waters in which they will be operating, such as sand, mud, rocks, etc. The anchor should be attached to a 3-6 foot length of galvanized chain, which resists abrasion better than a fiber line would and which helps to hold the anchor flat on the bottom so it can dig in more effectively. The chain, in turn, is attached to the anchor line. Together, they are known as the anchor rode.

The anchor rode should be long enough to enable the boater to pay out line at least seven times the likely depth of the water in which the vessel will be anchoring. Ideally, line should be made of nylon, which has an elasticity that enables it to stretch with the motion of the sea and helps reduce the shock load on both the anchor and the vessel. In choosing a spot in which to drop anchor, the operator should pick an area that offers maximum shelter from weather elements and boat traffic. Choose a bottom consisting of sand or hard mud which makes it more likely that the anchor’s flukes will dig in and hold. The anchor line should be paid out at least five to seven times the distance between the anchor chock at the vessel’s bow and the bottom. The operator and anyone who is going to help with the anchor should know how to properly set and weigh anchor. Different type anchors require different methods.

The anchor and rode become a life saving item whenever a boater is caught off guard by a change in the weather, which can cause wave action too strong to navigate. In this instance, a good anchor and rode can mean the difference between riding out the storm and sinking. Sometimes your only option is to anchor and play out enough anchor line so that the boat rides stationary in the water instead of being tossed about by the waves. Some experienced boaters carry more than one anchor, with a heavier anchor being reserved for such emergencies.

How Big an Anchor Do You Need?

A mistaken concept is that an anchor’s holding power depends on its weight. In truth, the anchor’s holding ability depends upon its design and upon matching a particular design to the type of bottom in which it is designed to hold. For the average recreational boat with a length of 16-26 feet, a utility anchor of between 12 and 18 pounds is satisfactory. A deeper draft vessel may need a little bit more anchor. Just as important as the type of anchor is the method in which it is deployed. If you intend to operate in areas with different types of bottoms, you may need more than one type of anchor. The most commonly used anchor in our area is the Danforth anchor. The second most common type used locally is the mushroom type. You may be interested to know that our navigation buoys use a mushroom type anchor.

Where Will You Be Anchoring?

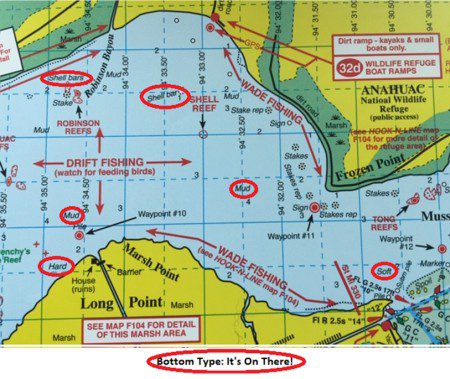

Bottom type is the most important consideration in choosing an anchor. Consult your navigation chart for your area. The bottom types are printed right on the chart. The predominant bottom types in our area are mud, sand, gravel, and oyster reef. The Danforth type anchor works well in mud, sand and gravel, but may not work as well on an oyster reef as a mushroom type anchor if the oyster clusters are very dense. I carry both a Danforth and a mushroom anchor in my boat, and can swap them out in about 10 seconds.

Storing the Anchor

I have performed VSCs on quite a few boats where the anchor is stored in a locker beneath what I call “everything else.” We don’t plan on an incident happening where we might need our anchor quickly, but we can sure plan FOR such an occasion. Your anchor should be stored in a location FOR IMMEDIATE USE. It should be stored free of any entanglements or fouling apparatus, and there should be ample room for the rode (chain and rope line) to run free. When you are dead in the water and drifting into an active and busy shipping lane like the Houston Ship Channel, this is not time to have to spend digging the anchor out and untangling the line. Also, do not store your anchor with a wet line. Rinse any salt water from the anchor, chain, and nylon line and allow it to air dry. Storing the anchor wet and unrinsed allows the chain to rust and the line to deteriorate.

Selecting the Anchorage

Always use your chart (or experience with a certain location) to help pick your anchorage. Try to pick an area that has little or no mud, no loose sand, and no grass. Almost every anchor does poorly in grass. Try to anchor with your bow into the wind. Keep in mind if you use only one anchor that you are free to swing 360 degrees, so pick an area that will not allow you to swing onto the land, rocks, or other structure that could damage your boat or cause your boat to damage a structure such as a dock or another boat anchored nearby. Also, choose an anchorage that will not allow your boat to swing out into a shipping lane.

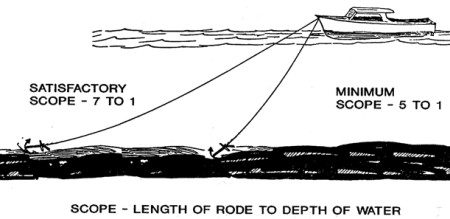

Anchoring- How Much Line to Pay Out

The amount of line you need to pay out in order to successfully anchor depends on the distance from the bow of the boat to the water bottom. We talk about the amount of line to pay out as a multiple of the distance from the bow to the water bottom. That multiple is called the scope. Basic seamanship manuals, including the US Coast Guard Seamanship Manual, recommend a scope 5 to 1 as a minimum, and a satisfactory scope in most cases is a scope of 7 to 1. If you want to anchor in water that is three feet deep and the distance from the bow to the water surface is two feet, then your scope would be (3+2) x 5 = 25 feet for a minimum amount of line to pay out, and (3+2) x 7 = 35 feet for a satisfactory amount of line to pay out. Yes, of course you may get by with less line. But if the tide changes and the current speed increases, you may suddenly find yourself quite a distance from where you first set the anchor. To help you judge how much line you have paid out, it is helpful to make marks on your line at regular intervals, say every 5 feet or so. A permanent marker on a white nylon line works quite well for that purpose. They also make plastic cable markers just for marking lengths on your anchor line.

Setting the Anchor

Be sure you are at dead stop before lowering the anchor over the side. If you are still moving forward, there is a good chance you may run over your anchor line and foul your propeller. When you are ready to lower the anchor, put your engine at idle and in reverse and slowly lower the anchor to the bottom. Pay out the rode until you get to your preselected marker or length, then take a turn or two around a cleat. Check to see that it is holding. A good set will hold your boat with the engine in reverse at idle. Once you are satisfied that the anchor is holding, you may then go to neutral and secure the rode to a cleat.

If the Anchor Drags

If the anchor drags, if there is no immediate danger of collision or grounding, and if you have room, let out additional scope and test for holding each time. You may have to weigh the anchor (pull it back in) and start over at a different spot if the bottom is grassy or too soft to hold. Besides the obvious movement when your anchor doesn’t hold, you can do environmental damage to the bottom by dragging your anchor, especially in protected sea grass areas.

Along with matching the anchor to the bottom type, the scope is a major factor in determining whether the anchor will hold.

Getting Underway

Always have your sails set or your engine running before breaking your anchor loose from the bottom. This will help prevent an unintentional grounding or a collision with another boat or structure. Try to clear any bottom debris such as mud or grass from your anchor before bringing it aboard, and do not let it swing into your hull. An anchor can do considerable damage to a wood or fiberglass hull. The person weighing the anchor should have some experience or at least some basic instruction so they don’t damage the hull or the deck when they retrieve the anchor.

Anchoring at Night

If you are anchoring at night or in reduced visibility, don’t forget to turn your navigation lights OFF and leave or turn on your anchor light. On most recreational boats, the all around light at the rear of the boat serves as the anchor light and the stern light.

Summary

Although not required, an anchor is an important safety device as well as a device to keep you on top of your favorite fishing spot, swimming spot, or your favorite spot to watch the world go by. There are some basic rules to help you anchor successfully, and by keeping your anchor and rode clean and ready to deploy, you will have a safer and more enjoyable trip on the water.

[BC: Mar-14-2023]

Posted in

Posted in