By Bob Currie, Vessel Examiner

By Bob Currie, Vessel Examiner

U. S. Coast Guard Auxiliary Flotilla 081-06-08

I am on the water quite a bit. My home is at the beach, and I can see ships in the Gulf of Mexico as well as barge tows and recreational boaters in the Intracoastal Waterway and Galveston East Bay. I see more than most people the different forces that act on a vessel’s hull, as well as the reactions of operators to those forces in regards to steering their vessels. This column will discuss the general forces involved and methods of dealing with such forces.

Flotilla 081-06-08 is based at Coast Guard Station Galveston. The Coast Guard Auxiliary is the uniformed civilian component of the US Coast Guard and supports the Coast Guard in nearly all mission areas. The Auxiliary was created by Congress in 1939. For more information, please visit www.cgaux.org.

Forces

There are many names for the different forces that act on a vessel’s hull. These forces cause the vessel to move in a particular direction or to change direction, as well as placing different stresses on the hull. Generally the force categories include environmental forces, propulsion, and steering. The environmental forces that affect the horizontal motion of a vessel are wind, seas, and current. In order to truly maintain control over your vessel, you must be aware of the environmental forces acting on your boat and use a combination of propulsion and steering to use or overcome those forces.

Wind Forces

The wind acts upon the portion of the boat that is above the waterline. The higher and broader your profile in the wind, the more the wind will affect your boat. Even the persons aboard add to your wind profile. Another name for your wind profile is “sail area.” The shape and portion of your boat below the waterline also affects how the boat handles in the wind. My old boat was a flat bottom boat with a very shallow draft, and it was greatly affected by the wind. A boat with a different hull shape and deeper draft is much less affected by the wind, but even subtle affects can have great significance when maneuvering close to the bank, maneuvering close to another vessel, or maneuvering close to a structure such as a pier. A sudden gust of wind can result in heavy damage when attempting to moor to a pier, so a greater understanding of the forces involved and how your boat handles under different conditions can save you a great deal of money.

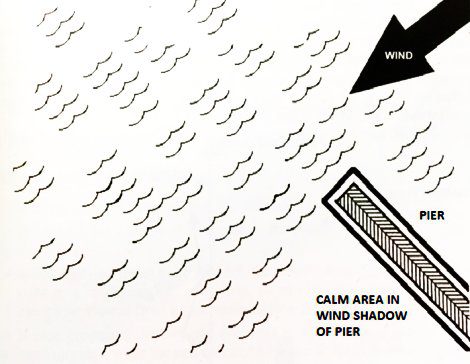

Wind Shadow

A wind shadow is a calm area caused by something such as a pier or other structure, or even a vessel, blocking a portion of the wind, thus reducing the wind force on your boat. Piers, docks, and jetties are often designed with the purpose of creating a wind shadow. The boat operator should look for any wind shadow the vessel or pier makes by blocking the wind, and plan maneuvers keeping the wind shadow in mind. A pennant or flag flown on your vessel can serve to alert you to any wind shadows. When maneuvering alongside another vessel, it is better to be in a wind shadow of that vessel than to be subject to the full force of the wind.

Seas

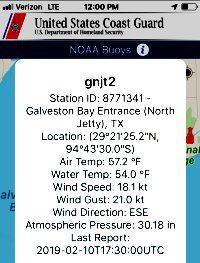

Seas are a product of the wind acting on the surface of the water. Seas affect boat handling in various ways, depending on their height and direction as well as the characteristics of the boat.  Smaller recreational boats are more likely to be affected by heavy seas than larger commercial vessels, and boat operators need to know when the seas are predicted to be too heavy for their boat. You should always check the weather before venturing out onto the water. One way to do that is to use the Coast Guard Safety app and click on the NOAA Buoys icon, then click on a buoy nearest to where you want to operate. An information window will pop up (example below).

Smaller recreational boats are more likely to be affected by heavy seas than larger commercial vessels, and boat operators need to know when the seas are predicted to be too heavy for their boat. You should always check the weather before venturing out onto the water. One way to do that is to use the Coast Guard Safety app and click on the NOAA Buoys icon, then click on a buoy nearest to where you want to operate. An information window will pop up (example below).

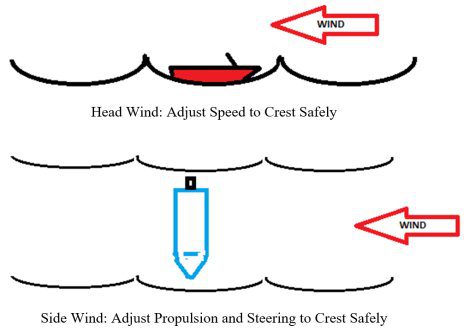

Relatively large seas sometimes create wind shadows for smaller vessels. In the trough between two wave crests the wind may be substantially less than the wind at the crest. Smaller boats may need to make corrective maneuvers in the trough before approaching the next crest, depending on the wind direction. The wind may affect maneuverability between wave crests. This is more the case when the wind direction is parallel to the wave crests. A boat that is heeled over sharply may be capsized by the wind when the boat crests a wave and the wind suddenly adds to the force causing the boat to heel over.

Current

Current acts upon the portion of the hull below the waterline much in the way wind acts on the portion above the waterline. The amount of draft will determine how much affect current will have. A one-knot current may affect a vessel to the same degree as a 30-knot wind. A strong current may easily move a vessel upwind. One-knot currents are normal in our area. In the example above the NOAA weather buoy at the entrance to Galveston Bay shows wind speed at 15.9 knots, wind gusts to 19 knots, and a wind direction of northwest.

As with the wind, a large stationary object like a breakwater or jetty will cause major changes in the amount and direction of current. Use caution when maneuvering in close quarters to buoys and anchored vessels. Be aware that tugboats that are holding barges against the shoreline create extremely strong currents with their engines, so give them a wide berth. You can also observe how wind and current affect other vessels. If a vessel is having a hard time maneuvering, you can be sure you will have a similar experience.

Know Your Boat’s Response

The boat operator should know how the vessel responds to combinations of wind and current, and determine which one has the greatest affect at any given combination. Be prepared for sudden gusts and changes in wind direction. Boats are often capsized by such sudden changes. When current goes against the wind, the wave patterns will be steeper and closer together. Rip current conditions frequently occur when the current goes against the wind.

Avoid heading directly into the wind where possible. Your fuel efficiency will be greatly reduced when fighting a head wind. The Coast Guard recommendation for fuel conservation is to use no more than 1/3 of your fuel going out. This will give you a fuel reserve that can get you back in safely if the weather changes against you.

Negotiating Head Seas

I call negotiating head seas “fighting your way home.” Boat operators should always look for the path of least resistance. The best way to get through waves is to avoid as many as possible. Do not try to steer a perfectly straight course in heavy seas. Instead, steer the smoothest course if navigation allows. Take advantage of any lulls between the higher series of waves. Work over each wave individually, varying speed and angle of attack to account for differences in each wave. Slow down and approach waves at an angle. Too much speed could launch the boat over the wave and result in a severe drop which could damage the hull. Continually adjust boat speed. Increase speed to keep the propeller in the water and working, but immediately reduce speed to minimize wave impact. Do not drive the bow into a wave.

Propulsion: Managing Power in Heavy Seas

Operators should keep one hand constantly on the throttle control. Use enough power to get the entire boat safely over or through the crest. Lighter boats will not carry momentum, so constant application of power is necessary. Keep a slight bow-up angle at all times. Once through the crest, a slight bow-up angle will let the after sections of the boat provide a good contact surface if the boat clears the water and will help to approach the next wave. Increase speed in the trough to counteract the reversed water flow and maintain directional control as the next wave approaches.

Staying in the Water

Flying through the crest should be avoided at all costs. If the vessel becomes airborne at the top of the wave, the crew is threatened with serious injury and the vessel could be damaged by the impact when the boat lands. If the bow sections get too high while going through a crest, the wind or the break could carry the bow over backward. On the other hand, if forward motion is lost with the stern at the crest, the bow might fall downward, making it necessary to redevelop speed and bow-up attitude before the next wave approaches.

Running Before a Sea

Operating in a following sea, especially in a breaking sea, involves the risk of the stern lifting up and being forced forward by the onrushing swell or breaker. Surfing down the face of the wave is extremely dangerous and nearly impossible to control. Surfing could cause the boat to capsize or to pitchpole end over end. Try to keep the boat ahead of breaking seas while maintaining control of both direction and speed. Some boats slip down the back of seas and heel strongly. Down swell heading should be made anywhere from directly down the swell to a 15-degree angle to the swells.

Avoid letting waves break over the transom of the boat. Vessels with outboard motors have relatively low transom wells that offer little protection from even a small breaking wave. A wave that breaks over the transom could fill the cockpit with water and swamp the boat. Without self-bailing, the vessel could capsize.

In waves with a wide regular pattern, boat operators should ride the back of the swell, and never ride on the front of the wave. On the front of the wave the boat may begin to surf, pushed along by the wave. As the bow nears the wave trough, it tends to dig in while the stern continues to be pushed. This sets up either a broadside broach or an end over end pitchpole as the breaking crest acts on the boat.

Coming About in Large Seas

Coming about, that is, making a turn in large seas can be dangerous. It puts the boat “beam (side) to the seas.” If it is necessary to come about before a wave, be careful not to use too much throttle and helm. Too much throttle could result in cavitation and leave no positive control in the face of the oncoming wave.

Traversing Beam Seas

In large beam seas, that is, where the waves hit the side of the boat rather than the bow or stern, the wave action will cause the boat to roll. The rolling will cause varying forces to affect steering. If this occurs, it is important to keep the propeller immersed. Going into deeper water will help to avoid breaking waves. Never get caught broadside to a breaking wave as it could capsize the boat. If the boat gets into seas that are spaced close together, look for an out.

Know When to Call for Help

The primary goal of any Coast Guard rescue is to save the occupants of the boat. Often it is too late to save the vessel, as the crew waited until they were in the process of swamping or capsizing before calling the Coast Guard. More vessels could have been saved if the occupants had called for assistance sooner. When waiting for assistance, be sure to update the Coast Guard with any changes in your position.

Heaving-To

If unable to reach safe haven, then heaving-to and riding out the severe weather might be the only option. Heaving-to is to park the boat while out at sea. Boat operators should maneuver only to keep a bow-on aspect to the weather. If unable to hold a heading, use a drogue as a sea anchor, made fast to the bow, to hold the boat into the weather. Make sure you have enough anchor line and rode to be able to anchor in any water you plan to negotiate. The rule of thumb is that you should pay out seven times the depth of the water in order to securely anchor, but in severe weather you may need much more line.

For more information on boating safety, please visit the Official Website of the U.S. Coast Guard’s Boating Safety Division at www.uscgboating.org. Questions about the US Coast Guard Auxiliary or our free Vessel Safety Check program may be directed to me at [email protected]. SAFE BOATING!

[Oct-4-2022]

Posted in

Posted in

Good article Bob, I have experienced several of these conditions, some with less than desired outcomes.