By Bob Currie, Recreational Boating Safety Specialist,

By Bob Currie, Recreational Boating Safety Specialist,

U. S. Coast Guard Auxiliary Station Galveston Flotilla

Every kid knows from watching the old movies about buried treasure that on the map to the buried treasure X marks the spot where to dig. That treasure map is only as good as its scale and reference points are, though, as Indiana Jones found out when he was looking for the Lost Ark and other such ancient relics.

The Station Galveston Flotilla of the US Coast Guard Auxiliary operates out of the USCG Station Galveston base on Galveston Island. They aid the Coast Guard by providing maritime observation patrols in Galveston Bay; by providing recreational boating vessel safety checks; and by working alongside Coast Guard members in maritime accident investigation, small boat training, providing a safety zone, Aids to Navigation verification, in the galley, on the Coast Guard Drone Team and watch standing.

Maps and Charts

Maps are what is used to navigate on dry land. On the water the proper term is chart. This is an especially important distinction to make on Talk Like a Pirate Day, aaarr!

Navigation

Navigation is the process of accurately ascertaining one’s position and following a route. You are navigating when you crank your car and head to the grocery store. Even though you don’t use a map to get there, you are using known reference points to guide you. You don’t need a map because you are very familiar with the route. You subconsciously use reference points to guide you: left on Elm Street and drive three blocks to Washington Boulevard, etc. If, however, you were like Drew Barrymore in Fifty First Dates and you had anterograde amnesia (loss of the ability to create new memories), you would need to use a map each time you wanted to go to the store.

Chart Scale: How Big a Boy Are Ya?

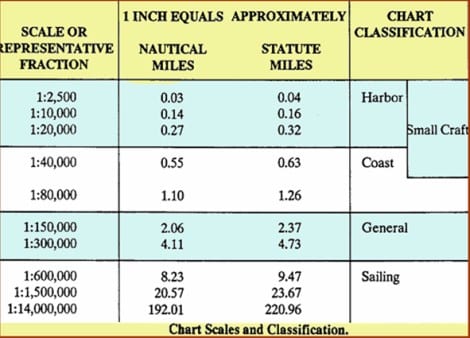

Two disc jockeys in Tulsa, Oklahoma used to make prank calls to people using the fictional character Roy D. Mercer to make the call. Mercer would demand that the call recipient pay him money for some incident, and if the recipient refused he would threaten them with violence (usually an ass-whuppin’). Mercer would then ask the recipient, “How big a boy are ya?” It’s kind of like that with charts. If you don’t have the right size chart, you might not want to use that chart to navigate. The larger the person, the less Roy D. Mercer wanted to fight the recipient. With charts, it is just the opposite. You want to use as large a scale chart as possible when using that chart for navigation. The larger the chart scale, that is, the smaller the second number in the scale, the more detail the chart shows. A 1:50,000 scale is larger scale than a 1:100,000 scale. It’s like that on a standard ruler, too. Half an inch (1/2”) is twice as large as a quarter inch (1/4”). There are five basic chart types:

- Sailing Charts: scale 1:600,000 and smaller; used offshore, outside of coastal areas, or between distant coastal ports

- General Charts: scale 1:150,000 to 1:600,000; used for offshore but within coastal zones outside of outlying reefs and shoals

- Coast Charts: scale 1:40,000 to 1:150,000; used for inshore navigation of bays and harbors of considerable width and for large inland waterways and coastal passages

- Harbor Charts: scale larger than 1:40,000; Used in harbors, anchorage areas and small waterways

- Small Craft Charts: scale larger than 1:40,000; composite type chart of inland waters containing information of interest to small boat operators. North on these charts may not necessarily be at the top of the chart. This is done so more detail can be fitted into the chart.

Let’s look at the scale a different way. For example, a Small Craft Chart scale may be 1:40,000. This means that one inch on the chart represents 40,000 inches of surface area. Dividing 40,000 by 12 inches to the foot gives you 3,333 feet. Divide 3,333 feet by 5280 feet to the mile gives you 0.63 miles. So, one inch on a 1:40,000 scale chart represents six tenths of a mile of surface area. The scale of the fishing chart I use for Galveston is 1:52,375. That scale is basically one inch equals eight tenths of a mile.

O Brother, Where Art Thou?

When we are under orders and on patrol we get that call from the Coast Guard watch stander every thirty minutes. They don’t quite say it that way, though. It is more like “Coast Guard Auxiliary Vessel 25145, Coast Guard Auxiliary Vessel 25145, Coast Guard Auxiliary Vessel 25145, Coasty Guard Station Galveston requesting Ops and position, over.” We have two ways of answering that call. One way is to give our bearing and distance from a reference point such as Eagle Point, except we use coded reference points. We might answer, “Coast Guard Station Galveston, this is Coast Guard Auxiliary Vessel 25145. Our position is 2.25 nautical miles bearing 45 degrees true from Banana, over.” We know that immediately by looking at our GPS, which is programmed to give us distance and bearing from Banana and several other coded reference points. We use this method when we operate using a Marine VHF/FM radio channel, which can be heard by anyone with a marine radio. As a recreational boater you could use a bearing and distance to report your position to the Coast Guard, but it would cause us some extra work trying to determine what we really need to know from you: your latitude and longitude. That doesn’t mean you can’t say “Coast Guard, we are approximately five miles due south of the end of the Galveston North Jetty, over.” We will find you fairly quickly with that position. But if you gave us latitude and longitude, we would be able to head directly to you without having to use a search pattern. When we are operating using a Coast Guard radio frequency, we report our position using latitude and longitude.

Parallels and Meridians

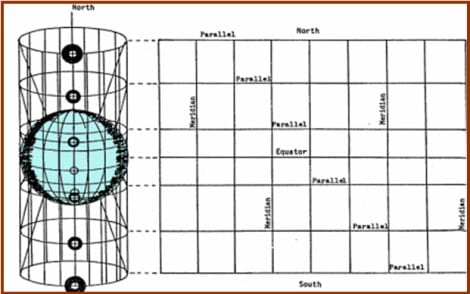

When map makers create a map, they are taking a spherical representation and projecting it onto a flat surface, unless they are making a globe of course. But although globes are great for seeing the big picture, they aren’t very handy for sea navigation. But flat maps always end up with some distortion in distance, direction and shape or area. One method of creating a map or chart for navigation purposes is the Mercator projection. The Mercator projection method is a cylindrical map projection. It became the standard map projection because of its unique property of representing any course of constant bearing as a straight line. Such a course representation is preferred in marine navigation because ships can sail in a constant compass direction for long stretches. Linear scale is constant on the Mercator projection in every direction around any point, thus preserving the angles and the shapes of small objects. One drawback is that the Mercator projection inflates the size of objects away from the equator. For instance, on a small scale projection such as a world map, Greenland appears as large as the United States, when in reality the United States is four times larger than Greenland.

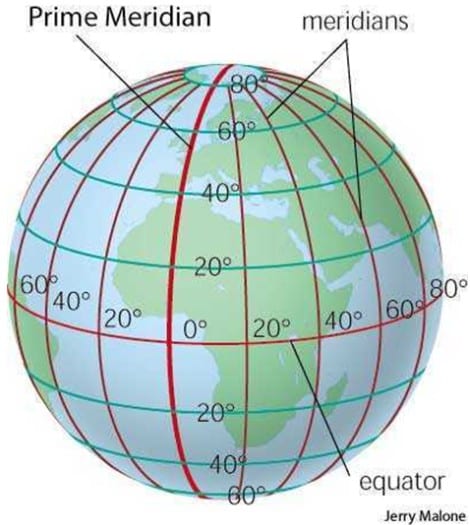

The Mercator projection has a horizontal and vertical grid that is used to help determine position on the surface. The grid lines are called parallels and meridians. The horizontal grid lines are called parallels. They are parallel to the equator. The vertical grid lines are called meridians.

All meridians cross each other at the north and the south pole. Parallels do not cross each other. On the globe here, the meridians are all in red, while the parallels, except for the red equator, are green colored. The meridian lines are also known as lines of longitude, while the parallels are known as lines of latitude. If you need a memory aid, think of latitude as flatitude, For longitude, remember Little Richard’s song, Long, Tall Sally.

Well long tall Sally

She’s really sweet

She got everything that Uncle John need

Oh baby

Yes baby

Wooh baby

Havin’ me some fun tonight, yeah

Latitude and Longitude

The latitude and longitude system allows us to use the parallels and meridians to precisely determine our location on the globe. The system uses as starting point where the equator passes through the Prime Meridian, also known as the Greenwich Meridian. The Greenwich Meridian is the longitudinal reference line that passes through the Royal Observatory, Greenwich, in London, England. The Greenwich Median is the meridian from which all other meridians are measured. Note that the prime meridian crosses the equator somewhere off the coast of Africa. That point can be described as zero degrees latitude/zero degrees longitude. Any other point on the globe is described as north or south of the equator, or east or west of the prime meridian. There is a point halfway around the globe from the Prime Meridian where it also crosses the equator. That meridian is called the antemeridian. It is also called the 180th meridian, and it mostly passes through the open waters of the Pacific Ocean. Another name for the 180th meridian is the international date line.

Location by Latitude

When giving your latitude, you must always give the number of the latitude followed by whether the latitude is north of or south of the equator. For instance, my location at my house is Latitude 29° 27’ 57” N (29 degrees, 27 minutes, and 57 seconds north of the equator). With latitude we can convert that location to miles quite easily: there are 60 miles to a degree, so I am located about 1,740 miles above the equator. Each hour, being 1/60th of a degree, is one mile, so we add 27 miles to the 1,740 figure to get 1,767 miles north of the equator. A second is 1/60th of a minute, or 88 feet. If we multiply 57 seconds times 88 feet we get 5,016 feet, or 0.95 miles. So, my latitude location is 1,767.95 miles north of the equator. The next step is to determine the Longitude, or my east-west position on the map or chart. We don’t have to do any of these calculations, however. We just must have a chart that includes Latitude 29 (plus or minus a few degrees) and is large enough scale to drill down to the minutes and seconds of my position.

Longitude

Longitude is the east-west measurement that begins at zero degrees (000°) at the Prime Meridian and is measured both east and west for 180°. Each degree of longitude is subdivided into 60 minutes, each of which is further subdivided into 60 seconds. As with the latitude determination, for a higher precision the seconds are specified with a fraction. At the equator, the distance between the medians is about 69 miles (24,902 miles divided by 360 degrees). However, as you move above or below the equator the distances between the medians becomes less since all meridians converge at the north and the south poles. Because of this phenomenon, we can’t use simple calculations to determine our distance from a reference point. Instead, we must use the longitude scale located on the top and bottom of the chart to determine the distance from a reference point. My Longitude at my house is 94° 36’ 43.1” W (94 degrees, 36 minutes, 43.1 seconds West of the Prime Meridian). This places me just a little over a fourth of the way around the globe westward from the Prime Meridian.

Summary

Whether you use a bearing and distance from a reference point or use Latitude and Longitude to describe your position on the globe, it is important to use as much precision as possible so that you can be located by the Coast Guard in an emergency. A GPS is the best way to accomplish both methods. Knowing where you are is important for general navigation purposes as well. In the grab shot below, the blue dot marks the spot (my location). I can use that blue dot to navigate to another location, such as one of the red balloons. Pay no attention to the locations of those balloons. They are not good fishing spots.

For more information on boating safety, please visit the Official Website of the U.S. Coast Guard’s Boating Safety Division at www.uscgboating.org. Questions about the US Coast Guard Auxiliary or our free Vessel Safety Check program may be directed to me at [email protected]. SAFE BOATING!

[Aug-3-2020]

Posted in

Posted in