By Bob Currie, Recreational Boating Safety Specialist

By Bob Currie, Recreational Boating Safety Specialist

U. S. Cast Guard Auxiliary Station Galveston Flotilla

One of the primary missions of the U.S. Coast Guard Auxiliary is Recreational Boating Safety (RBS). One way we increase RBS is by performing free Vessel Safety Checks. A Vessel Safety Check has two parts. The first part concerns Coast Guard regulations, and the second part concerns Coast Guard recommendations. The COVID69 Pandemic has put a damper on our ability to perform Vessel Safety Checks. This column and the previous column covers how you, with a little training from this column, can perform a self-check using the Coast Guard Vessel Safety Check form.

The Station Galveston Flotilla of the US Coast Guard Auxiliary operates out of the USCG Station Galveston base on Galveston Island. They aid the Coast Guard by providing maritime observation patrols in Galveston Bay; by providing recreational boating vessel safety checks; and by working alongside Coast Guard members in maritime accident investigation, small boat training, providing a safety zone, Aids to Navigation verification, in the galley, and watch standing.

Although your self-check will not rise to the quality of an inspection performed by an Auxiliarist, it will give you peace of mind until you can undergo an actual inspection by a Certified Vessel Examiner. The Vessel Safety Check discussed here is for both powered and sail vessels. We have a completely different version for Paddle Craft that will be discussed in another column. All the items below, while encouraged, are not requirements.

Marine Radio

I know that most recreational boaters rely on their cell phone for use in emergencies, but the Coast Guard recommends that boaters have a marine VHF-FM radio to use in contacting them in case of an emergency. With a VHF-FM marine radio, boaters are able to call for help if they need it, listen to updated weather forecasts and to Coast Guard broadcasts about other vessels in distress, and hear warnings from law enforcement authorities about hazards they may encounter.  Cell phones may seem like attractive substitutes to some boaters, but they aren’t nearly as good. Cell phones require that the boater know the telephone number of the first responder they want to contact, and they cannot receive area wide warnings that are broadcast over marine radio. Cell phones are not typically maritime friendly. Coverage is not guaranteed in many maritime environments. If you choose not to carry a marine VHF-FM radio, at least download the Coast Guard app to your cell phone. The app allows you to contact the Coast Guard directly in case of emergency. Calling 911 does not work well out on the water.

Cell phones may seem like attractive substitutes to some boaters, but they aren’t nearly as good. Cell phones require that the boater know the telephone number of the first responder they want to contact, and they cannot receive area wide warnings that are broadcast over marine radio. Cell phones are not typically maritime friendly. Coverage is not guaranteed in many maritime environments. If you choose not to carry a marine VHF-FM radio, at least download the Coast Guard app to your cell phone. The app allows you to contact the Coast Guard directly in case of emergency. Calling 911 does not work well out on the water.

With the new Digital Selective Calling (DSC) system and the Coast Guard’s Rescue 21 radio system, DSC VHF-FM radios serve as emergency beacons that can tell first-responders precisely where a vessel in distress is located when properly registered with a GPS input. These days, DSC VHF-FM marine radios are relatively inexpensive. A bulkhead mounted marine radio is best, since it has a greater range than a hand held model, but even a hand held radio will provide some protection. The best advice about VHF-FM marine radios is: For safety’s sake, don’t leave port without one. The Lowrance Link-5 radio is just one example of a reasonably priced (less than $200) marine radio.

Dewatering Device

A dewatering device is a piece of equipment designed to help bail out or pump out a boat. It isn’t required, but strongly recommended. It may be the only way to deal with a situation in which the vessel is taking on water. All boats should carry at least one effective manual dewatering device such as a hand operated pump, a bucket, or a large plastic bottle with the bottom cut off that can serve as a water scoop. This recommendation is in addition to any electrical or manual bilge pump that may have been installed on board. Installed bilge pumps should be periodically tested. Pontoon boats or vessels that do not have compartments vulnerable to flooding should carry at least one dewatering device in case they are called on to help other boaters. If you ever discovered after launching that you forgot to put in your plug, you will quickly realize the value of having additional help for that automatic bilge pump.

Mounted Fire Extinguishers

Fire extinguishers are not required to be mounted. It is strongly recommended that fire extinguishers be mounted in locations that are visible and readily accessible. Before a vessel gets under way, boat operators should show all crewmembers and passengers where fire extinguishers are located and how to operate them. The Coast Guard responds to vessel fires quite often. It is recommended that you have more fire extinguishers than required.

Anchor and Rode

Anchors also are an important piece of safety equipment to keep the boat from drifting into danger or running aground. Boaters should make sure that their boats are equipped with an anchor of the appropriate type, size and weight for their vessel, as well as the kind of bottom that prevails in the waters in which they will be operating, such as sand, mud, rocks, etc. The anchor should be attached to a 3-6 foot length of galvanized chain, which resists abrasion better than a fiber line would and which helps to hold the anchor flat on the bottom so it can dig in more effectively. The chain, in turn, is attached to the anchor line. Together, they are known as the anchor rode.

The anchor rode should be long enough to enable the boater to pay out line at least seven times the likely depth of the water in which the vessel will be anchoring. Ideally, line should be made of nylon, whose elasticity enables it to stretch with the motion of the sea and helps reduce the load on both the anchor and the vessel. In choosing a spot in which to drop anchor, the operator should pick an area that offers maximum shelter from weather elements and boat traffic. Choose a bottom consisting of sand or mud which makes it more likely that the anchor’s flukes will dig in and hold. The anchor line should be paid out at least five to seven times the distance between the anchor chock at the vessel’s bow and the bottom. The operator and anyone who is going to help with the anchor should know how to properly set and weigh anchor. Different type anchors require different methods.

The anchor and rode become a life-saving item whenever a boater is caught off guard by a change in the weather, which can cause wave action too strong to navigate. In this instance, a good anchor and rode can mean the difference between riding out the storm and sinking. Sometimes your only option is to anchor and play out enough anchor line so that the boat rides stationary in the water instead of being tossed about by the waves. Some experienced boaters carry more than one anchor, with a heavier anchor being reserved for such emergencies.

First Aid Kit and Rescue Gear

Boaters should carry a first aid kit properly sized and appropriate for the type of boating they do, such as on small lakes, coastal waters, offshore, or extended cruising. Adequate kits of all sizes can be purchased at boating supply stores or online. Boaters should also consider adding medicines or medical equipment that may be needed by crew members or passengers who have special medical conditions, such as allergies. Experienced fishermen know better than most boaters of the value of a well-supplied first aid kit. Although duct tape will serve to cover or close a gaping wound from a filet knife, wouldn’t you rather have a good roll of medical tape and antiseptic?

Operators also should consider carrying rescue equipment designed to help pull someone out of the water, such as extra life jackets; a life ring (or horseshoe buoy) with a polypropylene line tied to it; a line throw bag; or, on a sailboat, a rescue strop that can be wrapped around the chest of a person in the water so he or she can be hoisted aboard. Attaching a line to a life ring enables those on board to retrieve the device if it is tossed too far for the person in the water to reach; it also helps pull the person back to the boat once he or she grabs onto the life ring.

The operator should always make sure that the vessel’s propeller is stopped when a person in the water is near the boat; the best way to do that is to shut off the engine while the person is close by. This extra equipment is often referred to as a Man in Water (MIW) kit. The time to let your passengers know about this equipment is before you sail. Everyone should be apprised of the extent of and location of all safety equipment aboard before leaving the dock.

Visual Distress Signals on Inland Waters

Boaters operating on inland waters or locations where visual distress signals are not required should consider keeping them on board to enable them to signal other vessels or persons on land in case of emergency. Vessel owners should determine what types of signals they need based on the area and conditions in which their boats will be operating. The Coast Guard recommends that you have at least one daytime and one nighttime method of signaling distress.

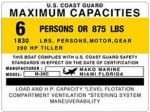

Capacity Plate

An overloaded boat has been the cause of many bad incidents on the water. The capacity plate, usually affixed to the transom, gunwale or on the center console of a recreational boat, contains important information about the limits under which the vessel should operate to ensure safety. It includes the maximum horsepower, the maximum number of persons and the maximum weight that may be carried (equipment and passengers combined). Capacity plates are required on mono-hull vessels under 20 feet in length. You may be tempted to take the number of persons on the capacity plate as the actual boat capacity, but if you take the time to do the math you will find that if you divide the “Persons” figure into the weight capacity, then the average person allowed for by the capacity plate weighs only 150 pounds. You should always consider both the number of persons capacity and the weight capacity and be governed by the most restrictive of the two. How many of you know the weight of your motor and the gear you bring aboard? The second weight capacity figure on the capacity plate is the total weight of persons, motor and gear. You should also keep that figure in mind when loading your boat with persons and gear. Picture in your mind, if you will, the scene from “Jaws” where all the boats are headed out to catch the great white shark, and most of the boats are grossly overloaded. The Richard Dreyfus character remarks, “They are all going to die.”

One last safety recommendation concerning capacity: once you have all your gear and persons aboard, check your freeboard. Freeboard is the distance from the water to the top of the gunnels at the lowest point. The counterpart to freeboard is the draft, the amount of boat below the water. Draft is not a fixed number; rather, it changes when your load changes. People always ask me what my draft is because my boat is designed for very shallow running. The answer is “it depends.” If I overload my boat, my draft increases and my freeboard decreases. You might know what your average draft is on your boat, but you won’t know for sure what the maximum draft is until you actually measure it under full load. I have 24 inch sides on my boat. If my freeboard is less than half that amount with all persons and gear aboard, I won’t leave the dock until I reduce weight considerably. Keep in mind also that salinity changes buoyancy. You will float higher in salt water than you will in fresh water with the same load.

One last safety recommendation concerning capacity: once you have all your gear and persons aboard, check your freeboard. Freeboard is the distance from the water to the top of the gunnels at the lowest point. The counterpart to freeboard is the draft, the amount of boat below the water. Draft is not a fixed number; rather, it changes when your load changes. People always ask me what my draft is because my boat is designed for very shallow running. The answer is “it depends.” If I overload my boat, my draft increases and my freeboard decreases. You might know what your average draft is on your boat, but you won’t know for sure what the maximum draft is until you actually measure it under full load. I have 24 inch sides on my boat. If my freeboard is less than half that amount with all persons and gear aboard, I won’t leave the dock until I reduce weight considerably. Keep in mind also that salinity changes buoyancy. You will float higher in salt water than you will in fresh water with the same load.

Accident Reporting

Boaters involved in a maritime accident are required to stop and render assistance to the extent that they can do so without endangering their own vessels, crewmembers, or passengers. When an accident occurs, it should be reported to authorities as required by federal, state, or local laws and regulations. If two boats are involved, the operators must provide one another with information about their vessels and the persons on board. Some states may vary in reporting times.

Federal law requires that reports be filed with the appropriate state agency for any boating accident that results in death; injury requiring medical treatment beyond first aid; damage totaling $2,000 or more to a vessel or other property; complete loss of a vessel; or the disappearance of a person under circumstances that indicates that death or injury is likely.

In cases involving deaths, disappearance, or injuries requiring medical treatment beyond first aid, local and state authorities must be notified within 48 hours. Reports on other accidents must be reported within 10 days. Some states may vary in reporting times. Each operator also must file a Recreational Boating Accident Report, Form CG-3865. Accident reporting requirements are also spelled out in the Coast Guard app.

Owner Responsibility

Under maritime law, the owner of a vessel may be held responsible for the safety and condition of his or her boat even if someone else is at the helm or if the owner is not on board and someone else is using the boat with his or her permission.

Offshore Operation – EPIRB, Life Raft, and Additional Communication Equipment

Boaters who operate offshore should carry additional equipment beyond that mandated by federal or state regulations. Among these items one may carry, depending upon how far from shore they intend to operate, are an Emergency Position Indicating Radio Beacon (EPIRB), which enables rescue personnel to determine a boat’s location; an inflatable life raft; an immersion suit for each person on board, if the vessel is to operate in cold waters; and VHF-FM or high-frequency transceivers suitable for the operating area, along with backup radios and cell phones.

Locator Beacons

An Emergency Position Indicating Radio Beacon (EPIRB) and Personal Locator Beacons (PLB) are used to alert search and rescue services in the event of an emergency. It does this by transmitting a coded message on the 406 MHZ distress frequency via satellite and earth stations to the nearest rescue coordination center. Some EPIRBS also have built-in GPS, which enables rescue services to accurately locate you +/- 125 meters.

A properly registered EPIRB and PLB are some of the most reliable and expeditious ways for the Coast Guard to receive notification of distress when properly registered and mounted. Registration is required by federal regulation (47 CFR 80.1061). Boaters should ensure that EPIRBs are mounted or stored securely and in a location that will enable the EPIRB to float free (ex. outside cabin for mounted EPIRB) or easily accessible (ex. in pants pocket or primary life jacket pocket for PLB) in case of capsize or other emergency. EPIRBs may be found in the $500-750 range.

While some are manual release, some have an automatic release feature in case of submersion. PLBs, designed to be attached to or carried in a person’s life jacket, may be found for around $250-350. Pictured below is an EPIRB with automatic release on the left and a PLB on the right.

Life Rafts

Life rafts can serve as a survival platform for an extended time. Operators should be sure that the raft is large enough to hold the maximum number of persons that will be aboard. The raft should be equipped with a package of appropriate emergency equipment (including food and water) and should be serviced professionally according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Although not cheap, a decent life raft may be purchased for around $1,000 fully equipped with visual distress signals.

Carbon Monoxide Dangers and Prevention

All boats with an engine are a source of carbon monoxide (CO). There are several recommendations from the Coast Guard for reducing boaters’ chances of being exposed to CO, and of course having a CO detector aboard is essential if you have an enclosed area where CO could accumulate, such as a cabin or a toilet.

- Inboard engines are now equipped with catalyst technology that greatly reduces the amount of CO flowing out of the exhaust system. Boats that are being re-engined should have the old gasoline engines replaced with catalyzed engines.

- Gasoline or propane generators that are installed on boats should be low or no CO engines.

- Houseboats should have low or no CO generators installed and should have a dewatered vertical stack exhaust system installed as shown in the American Boating and Yacht Council Standard P-1.

- All boats with enclosed accommodations should have marine rated CO detectors installed.

Nautical Charts

Nautical charts provide important information for navigating waterways and planning trips. They show the nature and shape of the coast, water depths, and characteristics of the bottom, prominent landmarks, port facilities, navigational aids, marine hazards, and other pertinent information. Charts are updated regularly by the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration and sold as print on demand through NOAA certified agents, marine supply stores and chart vendors. Boaters should be sure to use the most up to date charts available, and, when operating in coastal waters, obtain the largest scale charts they can, which show the greatest amount of detail about the area. Operators who use a chart plotter or GPS receiver in place of a paper chart should periodically buy or download updated charts. While fishing charts are great to have also, they should not be used for navigation.

Fuel Management

Boaters should take special precautions to avoid running out of fuel. One easy to remember formula is to allocate one third of the vessel’s total fuel supply for traveling to your destination, one third for returning to port, and one third to hold in reserve. This formula requires you to have good knowledge of your fuel consumption under different conditions. Your engine manufacturer may be able to help you by providing a fuel consumption table as a starting point. You should modify such table as necessary to fit your boat and load. This link will help you get started if your engine is an outboard model:

http://www.boat-fuel-economy.com/outboard-fuel-consumption-us-gallons .

Before you create your own fuel consumption table, it is wise to use your engine manufacturer’s reported maximum gallons per hour (GPH) usage as a starting point. The Yamaha interactive guide shown is based on moderate loads for a hypothetical boat, but it gives you a pretty good idea of the fuel usage based upon RPMs.

If you should find yourself becoming short on fuel on your way back in, the best thing you can do is reduce speed. Using the Yamaha 115 HP engine as an example, at 6000 RPM the engine consumes 9.7 GPH; at half speed (3000 RPM) it consumes 2.6 GPH; at one third speed (2000 RPM) it consumes 1.0 GPH. If you consider cruising speed to be three fourths throttle, the 115 HP Yamaha consumes 5.8 GPH at 4500 RPM. You almost double your fuel consumption from 4500 RPM to 6000 RPM. Working backwards from cruising speed, you can see that your fuel consumption drops dramatically. It might take you much longer to get home by reducing speed, but you will eventually get there! Hopefully you have filed a float plan and have that recommended marine radio aboard and you will not have to resort to critical measures to make it back to port.

If you should find yourself becoming short on fuel on your way back in, the best thing you can do is reduce speed. Using the Yamaha 115 HP engine as an example, at 6000 RPM the engine consumes 9.7 GPH; at half speed (3000 RPM) it consumes 2.6 GPH; at one third speed (2000 RPM) it consumes 1.0 GPH. If you consider cruising speed to be three fourths throttle, the 115 HP Yamaha consumes 5.8 GPH at 4500 RPM. You almost double your fuel consumption from 4500 RPM to 6000 RPM. Working backwards from cruising speed, you can see that your fuel consumption drops dramatically. It might take you much longer to get home by reducing speed, but you will eventually get there! Hopefully you have filed a float plan and have that recommended marine radio aboard and you will not have to resort to critical measures to make it back to port.

Float Plan

One of the most common problems the Coast Guard has when performing a Search and Rescue (SAR) mission is knowing where to start looking. Before shoving off from the pier, someone needs to know where you are going and when you expect to return, and that person should check on you if you don’t report in at the return time. The Coast Guard Auxiliary has all the information you need on creating and filing a float plan. You can go to the U.S. Coast Guard Auxiliary Float Plan Central website by following this link:

http://floatplancentral.cgaux.org/classroom/floatplans.htm.

Boating Check List

How can anyone remember all the required and recommended items and check their boat before starting their trip? It’s simple- create a check list that is tailored to your boat and go over that list before departing. The Vessel Safety Check is a good place to start when creating your checklist.

First Aid

Boaters are encouraged to take a first aid training course to prepare them to deal with medical emergencies that may arise while they are under way. First aid classes are available through the American Red Cross and other civic organizations. Some first aid courses include basic Cardiac Pulmonary Resuscitation (CPR) training. Many such courses are offered online, including CPR and First Aid courses.

Safe Boating Classes

All boaters born after August 31, 1993, must take a boater education course and have their certificate on board and available for inspection when operating a boat over a certain length and horsepower. Each state has different length and horsepower requirements. The Coast Guard recommends that all boaters take a boater education course. You can take a free course that is designed for your state. The link to the free courses is http://www.boatus.org/free/ .

Responsible Seamanship – Maritime Domain Awareness

Marine Domain Awareness means knowing what is going on in every direction and thinking in advance about how to deal with it. When a motorist drives along an interstate highway, he or she must not only watch the road that is directly ahead. The driver also has to keep an eye out for cars entering or preparing to exit the main highway; passing on either side; or tailgating too closely. If the road runs through the mountains, the motorist also may have to watch out for sudden curves; fallen rocks; or the absence of shoulders. The person steering (or in command of) a boat faces similar challenges. Is that cargo vessel steaming up the bay likely to pose a danger to the boat he or she is operating? If so, what action should the operator take? Slow down? Change course? A good helmsman is constantly checking for boat traffic, changes in sea state, weather patterns, and other factors affecting the boat, and relies on other crew members (and even some passengers) to help serve as lookouts. At the first sign of any changes, he or she begins making plans to deal with the new situation and to inform the crew on what action will be taken.

Insurance and Towing Considerations

Some states require proof of insurance before registering a vessel. In any case, it is a good idea to carry marine insurance. Although Texas does not require you to carry marine insurance, it is quite reasonably priced and gives you peace of mind. Among the items that may be covered by a marine insurance policy are loss of the boat, loss of equipment carried on board, protection against liability for personal injury or property damage, medical coverage in case of injury, and the cost of towing the boat in the water or carrying it by trailer on land.

Boaters should talk to an insurance agency about the kind of coverage that may be best for their boat. Coverage can be part of a homeowner policy or provided in a separate boat insurance policy. Towing insurance is often separate from liability insurance. Some companies may offer discounts to boaters who complete boating safety classes or whose boat passes a vessel safety check.

Summary

Although it is not designed to replace a Vessel Safety Check by a Certified Coast Guard Auxiliary Vessel Examiner, a self-check as outlined in this column can increase your chances of having a safe outing on the water. If you have ever had a Vessel Safety Check in the past, you have ready access to your Vessel Examiner, who can help you with any questions you may have about the Vessel Safety Check. Just look at the bottom of your previous Vessel Safety Check for the phone number of your Vessel Examiner, and don’t hesitate to call or text them with a question. The next column will cover the second half of the Vessel Safety Check, “Recommended and Discussion Items.”

For more information on boating safety, please visit the Official Website of the U.S. Coast Guard’s Boating Safety Division at www.uscgboating.org. Questions about the US Coast Guard Auxiliary or our free Vessel Safety Check program may be directed to me at [email protected]. SAFE BOATING!

[July-6-2020]

Posted in

Posted in

Thanks Bob , very informative